How To Build An ETL Using Python, Docker, PostgreSQL And Airflow

30 Min Read

Updated: 2022-02-18 06:54:15 +02:00

The Story

During the past few years, I have developed an interest in Machine Learning but never wrote much about the topic. In this post, I want to share some insights about the foundational layers of the ML stack. I will start with the basics of the ML stack and then move on to the more advanced topics.

This post will detail how to build an ETL (Extract, Transform and Load) using Python, Docker, PostgreSQL and Airflow.

You will need to sit down comfortably for this one, it will not be a quick read.

Before we get started, let’s take a look at what ETL is and why it is important.

One of the foundational layers when it comes to Machine Learning is ETL(Extract, Transform and Load). According to Wikipedia:

ETL is the general procedure of copying data from one or more sources into a destination system that represents the data differently from the source(s) or in a different context than the source(s). Data extraction involves extracting data from (one or more) homogeneous or heterogeneous sources; data transformation processes data by data cleaning and transforming it into a proper storage format/structure for the purposes of querying and analysis; finally, data loading describes the insertion of data into the final target database such as an operational data store, a data mart, data lake or a data warehouse.

One might begin to wonder, Why do we need an ETL pipeline?

Assume we had a set of data that we wanted to use. However, this data is unclean, missing information, and inconsistent as with most data. One solution would be to have a program clean and transform this data so that:

- There is no missing information

- Data is consistent

- Data is fast to load into another program

With smart devices, online communities, and E-Commerce, there is an abundance of raw, unfiltered data in today’s industry. However, most of it is squandered because it is difficult to interpret due to it being tangled. ETL pipelines are available to combat this by automating data collection and transformation so that analysts can use them for business insights.

There are a lot of different tools and frameworks that are used to build ETL pipelines. In this post, I will focus on how one can tediously build an ETL using Python, Docker, PostgreSQL and Airflow tools.

TL;DR

There’s no free lunch. Read the whole post.

The How

For this post, we will be using the data from UC-Irvine machine learning recognition datasets. This dataset contains Wine Quality information and it is a result of chemical analysis of various wines grown in Portugal.

We will need to extract the data from a public repository (for this post I went ahead and uploaded the data to https://gist.github.com/mmphego/5b6fc4d6dc3c8fba4fce9d994a2fe16b and transform it into a format that can be used by ML algorithms (not part of this post), thereafter we will load both raw and transformed data into a PostgreSQL database running in a Docker container, then create a DAG that will run an ETL pipeline periodically. The DAG will be used to run the ETL pipeline in Airflow.

The Walk-through

Before we can do any transformation, we need to extract the data from a public repository. Using Python and Pandas, we will extract the data from a public repository and upload the raw data to a PostgreSQL database. This assumes that we have an existing PostgreSQL database running in a Docker container.

The Setup

Let’s start by setting up our environment. First, we will set up our Jupyter Notebook and PostgreSQL database. Then, we will set up Apache Airflow (a fancy cron-like scheduler).

Setup PostgreSQL and Jupyter Notebook

In this section, we will set up the PostgreSQL database and Jupyter Notebook in a Docker container. First, we will need to create a .env file in the project directory. This file will contain the PostgreSQL database credentials which are needed in the docker-compose.yml file.

cat << EOF > .env

POSTGRES_DB=winequality

POSTGRES_USER=postgres

POSTGRES_PASSWORD=postgres

POSTGRES_HOST=database

POSTGRES_PORT=5432

EOF

Once we have the .env file, we can create a Postgres container instance that we will use as our Data Warehouse.

The code below will create a docker-compose.yaml file that will contain all the necessary information to run the container including a Jupyter Notebook that we can use to interact with the container and/or data.

cat << EOF > postgres-docker-compose.yaml

version: "3.8"

# Optional Jupyter Notebook service

services:

jupyter_notebook:

image: "jupyter/minimal-notebook"

container_name: ${CONTAINER_NAME:-jupyter_notebook}

environment:

JUPYTER_ENABLE_LAB: "yes"

ports:

- "8888:8888"

volumes:

- ${PWD}:/home/jovyan/work

depends_on:

- database

links:

- database

networks:

- etl_network

database:

image: "postgres:11"

container_name: ${CONTAINER_NAME:-database}

ports:

- "5432:5432"

expose:

- "5432"

environment:

POSTGRES_DB: "${POSTGRES_DB}"

POSTGRES_HOST: "${POSTGRES_HOST}"

POSTGRES_PASSWORD: "${POSTGRES_PASSWORD}"

POSTGRES_PORT: "${POSTGRES_PORT}"

POSTGRES_USER: "${POSTGRES_USER}"

healthcheck:

test:

[

"CMD",

"pg_isready",

"-U",

"${POSTGRES_USER}",

"-d",

"${POSTGRES_DB}"

]

interval: 5s

retries: 5

restart: always

volumes:

- /tmp/pg-data/:/var/lib/postgresql/data/

- ./init-db.sql:/docker-entrypoint-initdb.d/init.sql

networks:

- etl_network

volumes:

dbdata: null

# Create a custom network for bridging the containers

networks:

etl_network: null

EOF

But before we can run the container, we need to create the init-db.sql file that will contain the SQL command to create the database. This file will be our entrypoint into the container. Read more about Postgres Docker entrypoint here.

cat << EOF > init-db.sql

CREATE DATABASE ${POSTGRES_DB};

EOF

After creating the postgres-docker-compose.yaml file, we need to source the .env file, create a docker network (the docker network will ensure all containers are interconnected) and then run the docker-compose up command to start the container.

Note the current local directory is mounted to the /home/jovyan/work directory in the container. This is done to allow the container to access the data in the local directory. ie all the files in the local directory will be available in the container.

source .env

# Install yq (https://github.com/mikefarah/yq/#install) to parse the YAML file and retrieve the network name

NETWORK_NAME=$(yq eval '.networks' postgres-docker-compose.yaml | cut -f 1 -d':')

docker network create $NETWORK_NAME

# or hardcode the network name from the YAML file

# docker network create etl_network

docker-compose --env-file ./.env -f ./postgres-docker-compose.yaml up -d

When we run the docker-compose up command, we will see the following output:

Starting database_1 ... done

Starting jupyter_notebook_1 ... done

Since the container is running in detached mode, we will need to run the docker-compose logs command to see the logs and retrieve the URL of the Jupyter Notebook. The command below will print the URL (with access token) of the Jupyter Notebook.

docker logs $(docker ps -q --filter "ancestor=jupyter/minimal-notebook") 2>&1 | grep 'http://127.0.0.1' | tail -1

Once everything is running, we can open the Jupyter Notebook in the browser using the URL from the logs and have fun.

Setup Airflow

In this section, we will set up the Airflow environment. A quick overview of the Airflow environment, Apache Airflow, is an open-source tool for orchestrating complex computational workflows and creating a data processing pipeline. Think of it as a fancy version of a job scheduler or cron job. A workflow is a series of tasks that are executed in a specific order and we call them DAGs. A DAG (Directed Acyclic Graph) is a graph that contains a set of tasks that are connected by dependencies or a graph with nodes connected via directed edges.

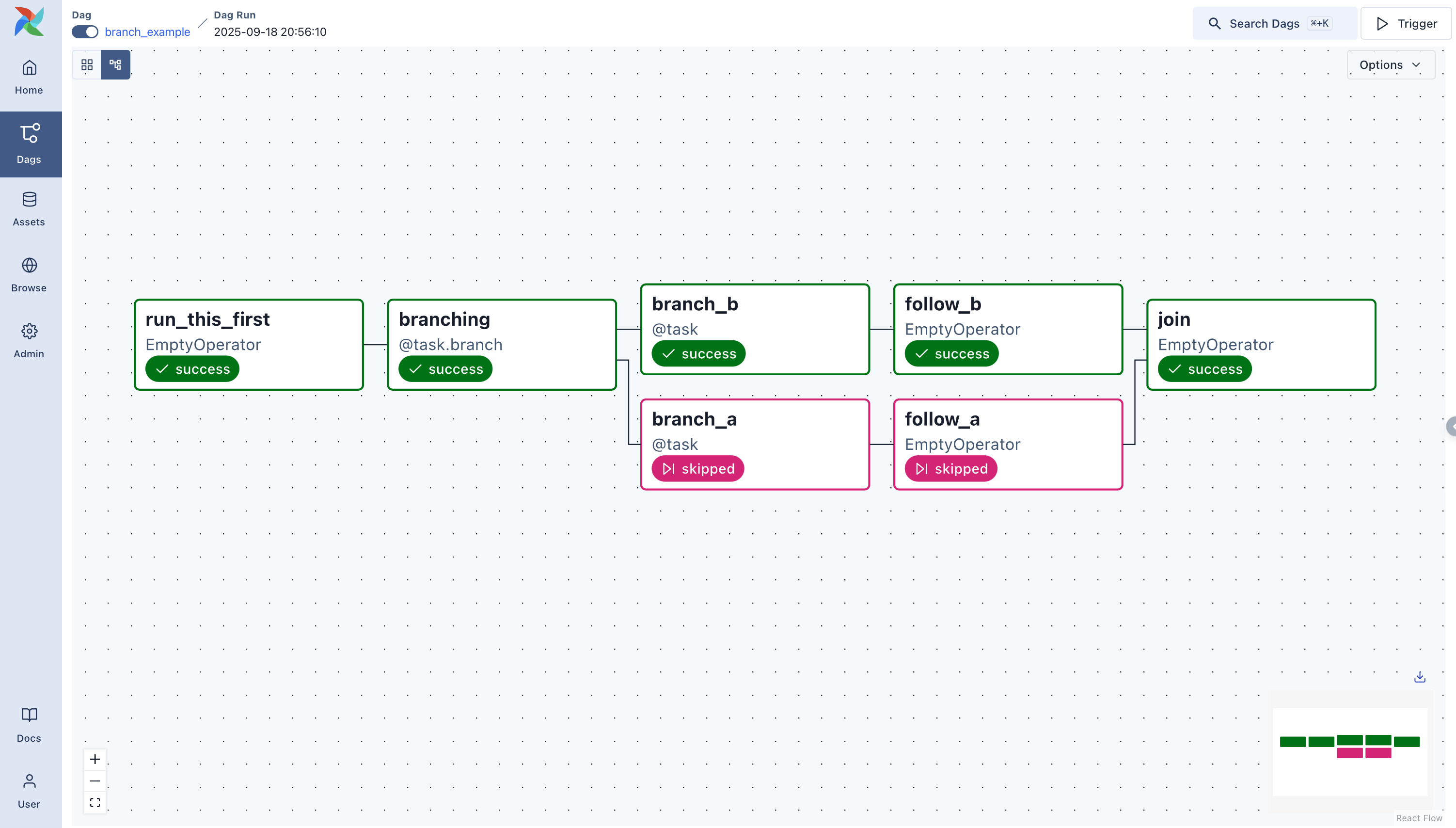

The image below shows an example of a DAG.

Read more about DAGs here: https://airflow.apache.org/docs/apache-airflow/stable/concepts/dags.html

Okay now that we got the basics of what Airflow and DAGs are, let’s set up Airflow. First, we will need to create our custom Airflow Docker image. This image adds and installs a list of Python packages that we will need to run the ETL (Extract, Transform and Load) pipeline.

First, let’s create a list of Python packages that we will need to install.

Run the following command to create the requirements.txt file:

cat << EOF > requirements.txt

pandas==1.3.5

psycopg2-binary==2.8.6

python-dotenv==0.19.2

SQLAlchemy==1.3.24

EOF

Then we will create a Dockerfile that will install the required Python packages (Ideally, we should only install packages in a virtual environment but for this post, we will install all packages in the Dockerfile).

cat << EOF > airflow-dockerfile

FROM apache/airflow:2.2.3

ADD requirements.txt /usr/local/airflow/requirements.txt

RUN pip install --no-cache-dir -U pip setuptools wheel

RUN pip install --no-cache-dir -r /usr/local/airflow/requirements.txt

EOF

Now we can create a Docker compose file that will run the Airflow container. The airflow-docker-compose.yaml below is a modified version of the official Airflow Docker. We have added the following changes:

- Customized Airflow image that includes the installation of Python dependencies.

- Removes example DAGs and reloads DAGs every 60seconds.

- Memory limitation set to 4GB.

- Allocated only 2 workers to run Gunicorn web server.

- Add our

.envfile to the Airflow container and, - A custom network for bridging the containers (Jupyter, PostgresDB and Airflow).

The airflow-docker-compose.yaml file when deployed will start a list of containers namely:

- airflow-scheduler - The scheduler monitors all tasks and DAGs, then triggers the task instances once their dependencies are complete.

- airflow-webserver - The webserver is available at http://localhost:8080.

- airflow-worker - The worker that executes the tasks given by the scheduler.

- airflow-init - The initialization service.

- flower - The flower app for monitoring the environment. It is available at http:/

- localhost:5555.

- postgres - The database.

- redis - The redis-broker that forwards messages from scheduler to worker.

cat << EOF > airflow-docker-compose.yaml

---

version: '3'

x-airflow-common:

&airflow-common

build:

context: .

dockerfile: airflow-dockerfile

environment:

&airflow-common-env

AIRFLOW__CORE__EXECUTOR: CeleryExecutor

AIRFLOW__CORE__SQL_ALCHEMY_CONN: postgresql+psycopg2://airflow:airflow@postgres/airflow

AIRFLOW__CELERY__RESULT_BACKEND: db+postgresql://airflow:airflow@postgres/airflow

AIRFLOW__CELERY__BROKER_URL: redis://:@redis:6379/0

AIRFLOW__CORE__FERNET_KEY: ''

AIRFLOW__CORE__DAGS_ARE_PAUSED_AT_CREATION: 'true'

AIRFLOW__CORE__LOAD_EXAMPLES: 'false'

AIRFLOW__API__AUTH_BACKEND: 'airflow.api.auth.backend.basic_auth'

# Scan for DAGs every 60 seconds

AIRFLOW__SCHEDULER__DAG_DIR_LIST_INTERVAL: '60'

AIRFLOW__WEBSERVER__SECRET_KEY: '3d6f45a5fc12445dbac2f59c3b6c7cb1'

# Prevent airflow from reloading the dags all the time and set:

AIRFLOW__SCHEDULER__MIN_FILE_PROCESS_INTERVAL: '60'

# 2 * NUM_CPU_CORES + 1

AIRFLOW__WEBSERVER__WORKERS: '2'

# Kill workers if they don't start within 5min instead of 2min

AIRFLOW__WEBSERVER__WEB_SERVER_WORKER_TIMEOUT: '300'

volumes:

- ./dags:/opt/airflow/dags

- ./logs:/opt/airflow/logs

- ./plugins:/opt/airflow/plugins

env_file:

- ./.env

user: "${AIRFLOW_UID:-50000}:${AIRFLOW_GID:-50000}"

mem_limit: 4000m

depends_on:

redis:

condition: service_healthy

postgres:

condition: service_healthy

networks:

- etl_network

services:

postgres:

image: postgres:13

environment:

POSTGRES_USER: airflow

POSTGRES_PASSWORD: airflow

POSTGRES_DB: airflow

volumes:

- postgres-db-volume:/var/lib/postgresql/data

healthcheck:

test: [ "CMD", "pg_isready", "-U", "airflow" ]

interval: 5s

retries: 5

restart: always

networks:

- etl_network

redis:

image: redis:latest

ports:

- 6379:6379

healthcheck:

test: [ "CMD", "redis-cli", "ping" ]

interval: 5s

timeout: 30s

retries: 50

restart: always

mem_limit: 4000m

networks:

- etl_network

airflow-webserver:

<<: *airflow-common

command: webserver

ports:

- 8080:8080

healthcheck:

test:

[

"CMD",

"curl",

"--fail",

"http://localhost:8080/health"

]

interval: 10s

timeout: 10s

retries: 5

restart: always

airflow-scheduler:

<<: *airflow-common

command: scheduler

healthcheck:

test:

[

"CMD-SHELL",

'airflow jobs check --job-type SchedulerJob --hostname

"$${HOSTNAME}"'

]

interval: 10s

timeout: 10s

retries: 5

restart: always

airflow-worker:

<<: *airflow-common

command: celery worker

healthcheck:

test:

- "CMD-SHELL"

- 'celery --app airflow.executors.celery_executor.app inspect ping -d

"celery@$${HOSTNAME}"'

interval: 10s

timeout: 10s

retries: 5

restart: always

airflow-init:

<<: *airflow-common

command: version

environment:

<<: *airflow-common-env

_AIRFLOW_DB_UPGRADE: 'true'

_AIRFLOW_WWW_USER_CREATE: 'true'

_AIRFLOW_WWW_USER_USERNAME: ${_AIRFLOW_WWW_USER_USERNAME:-airflow}

_AIRFLOW_WWW_USER_PASSWORD: ${_AIRFLOW_WWW_USER_PASSWORD:-airflow}

flower:

<<: *airflow-common

command: celery flower

ports:

- 5555:5555

healthcheck:

test: [ "CMD", "curl", "--fail", "http://localhost:5555/" ]

interval: 10s

timeout: 10s

retries: 5

restart: always

mem_limit: 4000m

volumes:

postgres-db-volume: null

# Create a custom network for bridging the containers

networks:

etl_network: null

EOF

Before starting Airflow for the first time, we need to prepare our environment. We need to add the Airflow USER to our .env file because some of the container’s directories that we mount, will not be owned by the root user. The directories are:

- ./dags - you can put your DAG files here.

- ./logs - contains logs from task execution and scheduler.

- ./plugins - you can put your custom plugins here.

The following commands will create the Airflow User & Group IDs and directories.

mkdir -p ./dags ./logs ./plugins

chmod -R 777 ./dags ./logs ./plugins

echo -e "AIRFLOW_UID=$(id -u)" >> .env

echo -e "AIRFLOW_GID=0" >> .env

After that, we need to initialize the Airflow database. We can do this by running the following command:

docker-compose -f airflow-docker-compose.yaml up airflow-init

This will create the Airflow database and the Airflow USER. Once we have the Airflow database and the Airflow USER, we can start the Airflow services.

docker-compose -f airflow-docker-compose.yaml up -d

Running docker ps will show us the list of containers running and we should make sure that the status of all containers is Up as shown in the image below.

Once we have confirmed that Airflow, Jupyter and database services are running, we can start the Airflow webserver.

The webserver is available at http://localhost:8080. The default account has the login airflow and the password airflow.

Now that all the hard work is done. We can create our ETL and DAGs.

Memory and CPU utilization

When all the containers are running, you can experience system lag if your system is not able to handle the load. Monitoring the CPU and Memory utilization of the containers is crucial to maintaining good performance and a reliable system. To monitor the CPU and Memory utilization of the containers, we use the Docker command-line tool stats command, which gives us a live look at our containers resource utilization. We can use this tool to gauge the CPU, Memory, Network, and disk utilization of every running container.

docker stats

The output of the above command will look like the following:

CONTAINER ID NAME CPU % MEM USAGE / LIMIT MEM % NET I/O BLOCK I/O PIDS

c857cddcac2b dataeng_airflow-scheduler_1 89.61% 198.8MiB / 3.906GiB 4.97% 2.49MB / 3.72MB 0B / 0B 3

b4be499c5e4f dataeng_airflow-worker_1 0.29% 1.286GiB / 3.906GiB 32.93% 304kB / 333kB 0B / 172kB 21

20af4408fd3d dataeng_flower_1 0.14% 156.1MiB / 3.906GiB 3.90% 155kB / 93.4kB 0B / 0B 74

075bb3178876 dataeng_airflow-webserver_1 0.11% 715.4MiB / 3.906GiB 17.89% 1.19MB / 808kB 0B / 8.19kB 30

967341194e93 dataeng_postgres_1 4.89% 43.43MiB / 15.26GiB 0.28% 4.85MB / 4.12MB 0B / 4.49MB 15

a0de99b6e4b5 dataeng_redis_1 0.12% 7.145MiB / 15.26GiB 0.05% 413kB / 428kB 0B / 4.1kB 5

6ad0eacdcfe2 jupyter_notebook 0.00% 128.7MiB / 15.26GiB 0.82% 800kB / 5.87MB 91.2MB / 12.3kB 3

4ba2e98a551a database 6.80% 25.97MiB / 15.26GiB 0.17% 19.7kB / 0B 94.2kB / 1.08MB 7

Clean Up

To stop and remove all the containers, including the bridge network, run the following command:

docker-compose -f airflow-docker-compose.yaml down --volumes --rmi all

docker-compose -f postgres-docker-compose.yaml down --volumes --rmi all

docker network rm etl_network

Extract, Transform and Load

Now that we have Jupyter, Airflow and Postgres services running, we can start creating our ETL. Open the Jupyter notebook and create a new notebook called Simple ETL.

Step 0: Install the required libraries

We need to install the required libraries for our ETL, these include:

- pandas: Used for data manipulation

- python-dotenv: Used for loading environment variables

- SQLAlchemy: Used for connecting to databases (Postgres)

- psycopg2: Postgres adapter for SQLAlchemy

!pip install -r requirements.txt

Step 1: Import libraries and load the environment variables

The first step is to import all the modules, load the environment variables and create the connection_uri variable that will be used to connect to the Postgres database.

import os

import pandas as pd

from dotenv import dotenv_values

from sqlalchemy import create_engine, inspect

CONFIG = dotenv_values('.env')

if not CONFIG:

CONFIG = os.environ

connection_uri = "postgresql+psycopg2://{}:{}@{}:{}".format(

CONFIG["POSTGRES_USER"],

CONFIG["POSTGRES_PASSWORD"],

CONFIG['POSTGRES_HOST'],

CONFIG["POSTGRES_PORT"],

)

Step 2: Create a connection to the Postgres database

We will treat this database as a fake production database, that will house both our raw and transformed data.

engine = create_engine(connection_uri, pool_pre_ping=True)

engine.connect()

Step 3: Extract the data from the hosting service

Once we have a connection to the Postgres database, we can pull a copy of the UC-Irvine machine learning recognition datasets that I recently uploaded to https://gist.github.com/mmphego

dataset = "https://gist.githubusercontent.com/mmphego/5b6fc4d6dc3c8fba4fce9d994a2fe16b/raw/ab5df0e76812e13df5b31e466a5fb787fac0599a/wine_quality.csv"

df = pd.read_csv(dataset)

It is always a good idea to check the data before you start working with it.

df.head()

| fixed acidity | volatile acidity | citric acid | residual sugar | chlorides | free sulfur dioxide | total sulfur dioxide | density | pH | sulphates | alcohol | quality | winecolor | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 7.0 | 0.27 | 0.36 | 20.7 | 0.045 | 45.0 | 170.0 | 1.0010 | 3.00 | 0.45 | 8.8 | 6 | white |

| 1 | 6.3 | 0.30 | 0.34 | 1.6 | 0.049 | 14.0 | 132.0 | 0.9940 | 3.30 | 0.49 | 9.5 | 6 | white |

| 2 | 8.1 | 0.28 | 0.40 | 6.9 | 0.050 | 30.0 | 97.0 | 0.9951 | 3.26 | 0.44 | 10.1 | 6 | white |

| 3 | 7.2 | 0.23 | 0.32 | 8.5 | 0.058 | 47.0 | 186.0 | 0.9956 | 3.19 | 0.40 | 9.9 | 6 | white |

| 4 | 7.2 | 0.23 | 0.32 | 8.5 | 0.058 | 47.0 | 186.0 | 0.9956 | 3.19 | 0.40 | 9.9 | 6 | white |

We also need to have an understanding of the data types that we will be working with. This will give us a clear indication of some features we need to engineer or any missing values that we need to fill in.

df.info()

<class 'pandas.core.frame.DataFrame'>

RangeIndex: 6497 entries, 0 to 6496

Data columns (total 13 columns):

# Column Non-Null Count Dtype

--- ------ -------------- -----

0 fixed acidity 6497 non-null float64

1 volatile acidity 6497 non-null float64

2 citric acid 6497 non-null float64

3 residual sugar 6497 non-null float64

4 chlorides 6497 non-null float64

5 free sulfur dioxide 6497 non-null float64

6 total sulfur dioxide 6497 non-null float64

7 density 6497 non-null float64

8 pH 6497 non-null float64

9 sulphates 6497 non-null float64

10 alcohol 6497 non-null float64

11 quality 6497 non-null int64

12 winecolor 6497 non-null object

dtypes: float64(11), int64(1), object(1)

memory usage: 660.0+ KB

From the above information, we can see that there are a total of 6497 rows and 13 columns. But the 13th column is the winecolor column and it does not contain numerical values. We need to convert/transform this column into numerical values.

Now, let’s check the table summary which gives us a quick overview of the data this includes the count, mean, standard deviation, min, max, 25th percentile, 50th percentile, 75th percentile, and the number of null values.

df.describe()

| fixed acidity | volatile acidity | citric acid | residual sugar | chlorides | free sulfur dioxide | total sulfur dioxide | density | pH | sulphates | alcohol | quality | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| count | 6497.000000 | 6497.000000 | 6497.000000 | 6497.000000 | 6497.000000 | 6497.000000 | 6497.000000 | 6497.000000 | 6497.000000 | 6497.000000 | 6497.000000 | 6497.000000 |

| mean | 7.215307 | 0.339666 | 0.318633 | 5.443235 | 0.056034 | 30.525319 | 115.744574 | 0.994697 | 3.218501 | 0.531268 | 10.491801 | 5.818378 |

| std | 1.296434 | 0.164636 | 0.145318 | 4.757804 | 0.035034 | 17.749400 | 56.521855 | 0.002999 | 0.160787 | 0.148806 | 1.192712 | 0.873255 |

| min | 3.800000 | 0.080000 | 0.000000 | 0.600000 | 0.009000 | 1.000000 | 6.000000 | 0.987110 | 2.720000 | 0.220000 | 8.000000 | 3.000000 |

| 25% | 6.400000 | 0.230000 | 0.250000 | 1.800000 | 0.038000 | 17.000000 | 77.000000 | 0.992340 | 3.110000 | 0.430000 | 9.500000 | 5.000000 |

| 50% | 7.000000 | 0.290000 | 0.310000 | 3.000000 | 0.047000 | 29.000000 | 118.000000 | 0.994890 | 3.210000 | 0.510000 | 10.300000 | 6.000000 |

| 75% | 7.700000 | 0.400000 | 0.390000 | 8.100000 | 0.065000 | 41.000000 | 156.000000 | 0.996990 | 3.320000 | 0.600000 | 11.300000 | 6.000000 |

| max | 15.900000 | 1.580000 | 1.660000 | 65.800000 | 0.611000 | 289.000000 | 440.000000 | 1.038980 | 4.010000 | 2.000000 | 14.900000 | 9.000000 |

Looking at the data, we can see a few things:

- Since our data contains categorical variables (winecolor), we can use one-hot encoding to transform the categorical variables into binary variables

- We can normalize the data by transforming it to have zero mean, this will ensure that the data is centred around zero ie standardize the data

Step 4: Transform the data into usable format

Now that we have an idea of what our data looks like, we can use the pandas.get_dummies function to transform the categorical variables into binary variables then drop the original categorical variables.

df_transform = df.copy()

winecolor_encoded = pd.get_dummies(df_transform['winecolor'], prefix='winecolor')

df_transform[winecolor_encoded.columns.to_list()] = winecolor_encoded

df_transform.drop('winecolor', axis=1, inplace=True)

Then we can normalize the data by subtracting the mean and dividing by the standard deviation. This will ensure that the data is centred around zero and has a standard deviation of 1. Instead of using sklearn.preprocessing.StandardScaler, we will use the z-score normalization (also known as standardization) method.

for column in df_transform.columns:

df_transform[column] = (df_transform[column] -

df_transform[column].mean()) / df_transform[column].std()

After transforming the data, we can now take a look:

df_transform.head()

| fixed acidity | volatile acidity | citric acid | residual sugar | chlorides | free sulfur dioxide | total sulfur dioxide | density | pH | sulphates | alcohol | quality | winecolor_red | winecolor_white | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | -0.166076 | -0.423150 | 0.284664 | 3.206682 | -0.314951 | 0.815503 | 0.959902 | 2.102052 | -1.358944 | -0.546136 | -1.418449 | 0.207983 | -0.571323 | 0.571323 |

| 1 | -0.706019 | -0.240931 | 0.147035 | -0.807775 | -0.200775 | -0.931035 | 0.287595 | -0.232314 | 0.506876 | -0.277330 | -0.831551 | 0.207983 | -0.571323 | 0.571323 |

| 2 | 0.682405 | -0.362411 | 0.559923 | 0.306184 | -0.172231 | -0.029596 | -0.331634 | 0.134515 | 0.258100 | -0.613338 | -0.328496 | 0.207983 | -0.571323 | 0.571323 |

| 3 | -0.011807 | -0.666110 | 0.009405 | 0.642474 | 0.056121 | 0.928182 | 1.242978 | 0.301255 | -0.177258 | -0.882144 | -0.496181 | 0.207983 | -0.571323 | 0.571323 |

| 4 | -0.011807 | -0.666110 | 0.009405 | 0.642474 | 0.056121 | 0.928182 | 1.242978 | 0.301255 | -0.177258 | -0.882144 | -0.496181 | 0.207983 | -0.571323 | 0.571323 |

Then check how the data looks like after normalization:

df_transform.describe()

| fixed acidity | volatile acidity | citric acid | residual sugar | chlorides | free sulfur dioxide | total sulfur dioxide | density | pH | sulphates | alcohol | quality | winecolor_red | winecolor_white | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| count | 6.497000e+03 | 6.497000e+03 | 6.497000e+03 | 6.497000e+03 | 6.497000e+03 | 6.497000e+03 | 6497.000000 | 6.497000e+03 | 6.497000e+03 | 6.497000e+03 | 6.497000e+03 | 6.497000e+03 | 6.497000e+03 | 6.497000e+03 |

| mean | 2.099803e-16 | -2.449770e-16 | 3.499672e-17 | 3.499672e-17 | -3.499672e-17 | -8.749179e-17 | 0.000000 | -3.517170e-15 | 2.720995e-15 | 2.099803e-16 | -8.399212e-16 | -2.821610e-16 | -3.499672e-17 | 1.749836e-16 |

| std | 1.000000e+00 | 1.000000e+00 | 1.000000e+00 | 1.000000e+00 | 1.000000e+00 | 1.000000e+00 | 1.000000 | 1.000000e+00 | 1.000000e+00 | 1.000000e+00 | 1.000000e+00 | 1.000000e+00 | 1.000000e+00 | 1.000000e+00 |

| min | -2.634386e+00 | -1.577208e+00 | -2.192664e+00 | -1.017956e+00 | -1.342536e+00 | -1.663455e+00 | -1.941631 | -2.529997e+00 | -3.100376e+00 | -2.091774e+00 | -2.089189e+00 | -3.227439e+00 | -5.713226e-01 | -1.750055e+00 |

| 25% | -6.288845e-01 | -6.661100e-01 | -4.722972e-01 | -7.657389e-01 | -5.147590e-01 | -7.620156e-01 | -0.685480 | -7.858922e-01 | -6.748102e-01 | -6.805395e-01 | -8.315512e-01 | -9.371575e-01 | -5.713226e-01 | 5.713226e-01 |

| 50% | -1.660764e-01 | -3.016707e-01 | -5.940918e-02 | -5.135217e-01 | -2.578628e-01 | -8.593639e-02 | 0.039904 | 6.448391e-02 | -5.287017e-02 | -1.429263e-01 | -1.608107e-01 | 2.079830e-01 | -5.713226e-01 | 5.713226e-01 |

| 75% | 3.738663e-01 | 3.664680e-01 | 4.911081e-01 | 5.584015e-01 | 2.559297e-01 | 5.901428e-01 | 0.712210 | 7.647937e-01 | 6.312639e-01 | 4.618885e-01 | 6.776148e-01 | 2.079830e-01 | -5.713226e-01 | 5.713226e-01 |

| max | 6.698910e+00 | 7.533774e+00 | 9.230570e+00 | 1.268585e+01 | 1.584097e+01 | 1.456245e+01 | 5.736815 | 1.476765e+01 | 4.922650e+00 | 9.870119e+00 | 3.695947e+00 | 3.643405e+00 | 1.750055e+00 | 5.713226e-01 |

Step 5: Ingest the data into a database

If we are happy with the results, then we can ingest both dataframes into our database. Since we do not have any tables in our database and our dataset is small, we can get away by using the .to_sql method to write the data to a table in the database.

raw_table_name = 'raw_wine_quality_dataset'

df.to_sql(raw_table_name, engine, if_exists='replace')

transformed_table_name = 'clean_wine_quality_dataset'

df_transformed.to_sql(transformed_table_name, engine, if_exists='replace')

This will create two tables in our database, namely raw_wine_quality_dataset and clean_wine_quality_dataset.

For a sanity check, we can verify that the data in both tables were successfully written to the database, using the following query:

def check_table_exists(table_name, engine):

if table_name in inspect(engine).get_table_names():

print(f"{table_name!r} exists in the DB!")

else:

print(f"{table_name} does not exist in the DB!")

check_table_exists(raw_table_name, engine)

check_table_exists(transformed_table_name, engine)

Well, that was a lot of work! But, we can do even better! We can use the .read_sql method to read the data from the database and then use the .drop_duplicates method to remove the duplicate rows.

pd.read_sql(f"SELECT * FROM {raw_table_name}", engine)

pd.read_sql(f"SELECT * FROM {transformed_table_name}", engine)

Well done, we successfully wrote our data into the database. Our ETL pipeline is now complete the only thing left to do is to make it repeatable via Airflow.

Airflow ETL Pipeline

Now that we have an ETL pipeline that can be run in Airflow, we can start building our Airflow DAG.

We can reuse our jupyter notebook and ensure that the DAG is written to file as a Python script by using the magic command %%writefile dags/simple_etl_dag.py

Step 1: Import necessary

But first, we need to import the necessary libraries and to create a DAG in Airflow, you always have to import the DAG class from airflow.models. Then import the PythonOperator (since we will be executing Python logic) and finally, import days_ago to get a datetime object representation of n days ago.

import os

from functools import wraps

import pandas as pd

from airflow.models import DAG

from airflow.utils.dates import days_ago

from airflow.operators.python import PythonOperator

from dotenv import dotenv_values

from sqlalchemy import create_engine, inspect

Step 2: Create a DAG object

After importing the necessary libraries, we can create a DAG object. We will use the DAG class from airflow.models to create a DAG object. A DAG object must have a dag_id, a schedule_interval, and a start_date. The dag_id is a unique name of the DAG, and the schedule_interval is the interval at which the DAG will be executed. The start_date is the date at which the DAG will start. We can also add a default_args parameter to the DAG object, which is a dictionary of default arguments that may include Owners information, a description, and a default start_date.

args = {"owner": "Airflow", "start_date": days_ago(1)}

dag = DAG(dag_id="simple_etl_dag", default_args=args, schedule_interval=None)

Step 3: Define a logging function

For the sake of simplicity, we will create a simple (decorator) logging function that will be used to log the execution of the DAG using print statements of course.

def logger(func):

from datetime import datetime, timezone

@wraps(func)

def wrapper(*args, **kwargs):

called_at = datetime.now(timezone.utc)

print(f">>> Running {func.__name__!r} function. Logged at {called_at}")

to_execute = func(*args, **kwargs)

print(f">>> Function: {func.__name__!r} executed. Logged at {called_at}")

return to_execute

return wrapper

Step 4: Create an ETL function

We will refactor the ETL pipeline we defined above into be a function that can be called by the DAG and use the logger function to log the execution of the function.

DATASET_URL = "https://gist.githubusercontent.com/mmphego/5b6fc4d6dc3c8fba4fce9d994a2fe16b/raw/ab5df0e76812e13df5b31e466a5fb787fac0599a/wine_quality.csv"

CONFIG = dotenv_values(".env")

if not CONFIG:

CONFIG = os.environ

@logger

def connect_db():

print("Connecting to DB")

connection_uri = "postgresql+psycopg2://{}:{}@{}:{}".format(

CONFIG["POSTGRES_USER"],

CONFIG["POSTGRES_PASSWORD"],

CONFIG["POSTGRES_HOST"],

CONFIG["POSTGRES_PORT"],

)

engine = create_engine(connection_uri, pool_pre_ping=True)

engine.connect()

return engine

@logger

def extract(dataset_url):

print(f"Reading dataset from {dataset_url}")

df = pd.read_csv(dataset_url)

return df

@logger

def transform(df):

# transformation

print("Transforming data")

df_transform = df.copy()

winecolor_encoded = pd.get_dummies(df_transform["winecolor"], prefix="winecolor")

df_transform[winecolor_encoded.columns.to_list()] = winecolor_encoded

df_transform.drop("winecolor", axis=1, inplace=True)

for column in df_transform.columns:

df_transform[column] = (

df_transform[column] - df_transform[column].mean()

) / df_transform[column].std()

return df

@logger

def check_table_exists(table_name, engine):

if table_name in inspect(engine).get_table_names():

print(f"{table_name!r} exists in the DB!")

else:

print(f"{table_name} does not exist in the DB!")

@logger

def load_to_db(df, table_name, engine):

print(f"Loading dataframe to DB on table: {table_name}")

df.to_sql(table_name, engine, if_exists="replace")

@logger

def tables_exists():

db_engine = connect_db()

print("Checking if tables exists")

check_table_exists("raw_wine_quality_dataset", db_engine)

check_table_exists("clean_wine_quality_dataset", db_engine)

db_engine.dispose()

@logger

def etl():

db_engine = connect_db()

raw_df = extract(DATASET_URL)

raw_table_name = "raw_wine_quality_dataset"

clean_df = transform(raw_df)

clean_table_name = "clean_wine_quality_dataset"

load_to_db(raw_df, raw_table_name, db_engine)

load_to_db(clean_df, clean_table_name, db_engine)

db_engine.dispose()

Step 5: Create a PythonOperator

Now that we have our ETL function defined, we can create a PythonOperator that will execute the ETL and data verification function. One of the best practices is to use context managers thus avoiding the need to add dag=dag to your task which might result in Airflow errors.

with dag:

run_etl_task = PythonOperator(task_id="run_etl_task", python_callable=etl)

run_tables_exists_task = PythonOperator(

task_id="run_tables_exists_task", python_callable=tables_exists)

run_etl_task >> run_tables_exists_task

That’s it! Now, we can head out to the Airflow UI and check if our DAG was created successfully.

Step 6: Run the DAG

After we log in to the Airflow UI, we should notice that the DAG was created successfully. You should see an image similar to the one below.

If we are happy with the DAG, we can now run the DAG by clicking on the green play button and selecting Trigger DAG. This will start the DAG execution

Let’s open the last successful run of the DAG and see the logs. The image below shows the graph representation of the DAG

Looks like the DAG was executed successfully, everything is Green! Now, we can check the logs of the DAG to see the execution of the ETL function by clicking on an individual task and then clicking on the Logs tab.

The logs show that the ETL function was executed successfully.

This now concludes this post. If you have gotten this far, I hope you enjoyed this post and found it useful.

Conclusion

In this post, We have covered the basics of creating your very own ETL pipeline, how to run multiple docker containers interconnected, Data manipulation and feature engineering techniques, simple techniques on reading and writing data to a database, and finally, how to create a DAG in Airflow. This has been a great learning experience and I hope you found this post useful. In the next post, I will explore a less tedious way of creating an ETL pipeline using AWS services. So stick around and learn more!

FYI it took me a week to write this post. I was trying to get a better understanding of Docker networking, Postgres Fundamentals, Airflow ecosystem and how to create a DAG. This was a great learning experience and I hope you found this post useful.

Code used in this post is available on https://github.com/mmphego/simple-etl